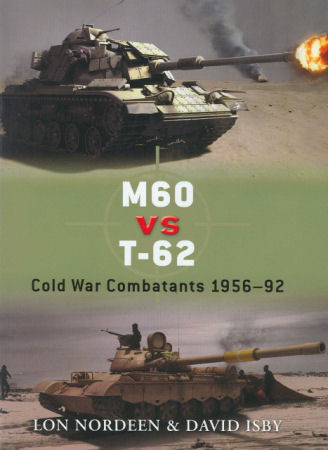

M60 vs T-72 Book Review

By Cookie Sewell

| Date of Review | December 2010 | Title | M60 vs T-72 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Lon Nordeen and David Isby | Publisher | Osprey Publishing |

| Published | 2010 | ISBN | 978-1-84603-694-1 |

| Format | 80 pages, softcover | MSRP (USD) | $17.95 |

Review

When Soviet Ground Forces commander Marshal Valeriy Chuykov found out that the British were going to install the 105mm L7 gun in an improved variant of the Centurion tank, and the Americans and Germans planned to use the same gun in their new medium tanks, he really did go ballistic. Demanding that the Soviets had to have a bigger tank in the field even if “you have to strap it on the back of a pig” his demand to the military industrial complex set in motion one of the great parings of the cold war – what emerged as the Soviet T-62 in the hands of its client states versus the US and its allies armed with the M60 main battle tank.

Neither one was a very original design – both evolved from proven designs. The T-62 was a modified T-55 tank that was reworked to fit the big 115mm U-5TS gun onto a medium tank chassis; the M60 combined the best ideas of the day with design improvements to the M48A2 medium tank to come up with a diesel powered and 105mm armed tank.

Both tanks evolved due to continual failures to develop breakthrough tank designs. The T-62 came about due to massive problems with the radical Article 430 and Article 432 tank design (later to become the T-64 series tanks) but using the same 115mm gun the evolved Article 432 was mounting. Chuykov’s demand for the big gun could not be fulfilled in a reasonable amount of time due to the teething troubles the new tank had – this was the late 1950s and the T-64 did not become viable until 1969. Leonid Kartsev said that his design bureau at Nizhniy Tagil could get the gun on a tank in less than a year. But the Ministry of Defense refused to put two tanks with identical guns into service at once, so when the T-62 was accepted for service in 1961 it was as a “tank destroyer” and not a tank. (20,000 tanks later, this little definition deviation was clearly ignored.)

Ditto the M60. The future US tank program at the time was the T95 with a totally new chassis, new turret, new gun and new features all around. But with the failure of the T95 program a new design had to be created in a hurry. Design features like the new glacis design, the 105mm M68 (license built L7) and a big AVDS-1790 series diesel engine were used to create the new interim tank that became the M60.

Both tanks evolved as well. By 1965 the M60 had received a new turret with a thinner front profile and wide bustle to become the M60A1; in 1972 the T-62 gave up the pretense of being a “tank destroyer” and added a 12.7mm AA machine gun.

Incidentally both tanks had an outlier tank destroyer variant armed with missiles: the IT-1 with the “Drakon” missile and the M60A2 “Starship” with the Shillelagh. Neither one was very popular and both were only seen as short term solutions.

While thousands of these tanks were soon populating divisions stationed in East and West Germany, the first actual clash between them came during the Yom Kippur war in 1973. The IDF fought with both the Egyptians at the Battle of Chinese Farm and with the Syrians and Iraqis on the Golan Heights. However, while the T-62 fought in both areas the M60s were only used against the Egyptians (upgunned Centurions with that same L7 gun were able to stop and destroy most of the Syrian and Iraqi T-62s at the “Vale of Tears”.)

The results of the Chinese Farm battle were very one-sided. The M60A1 tanks used by the IDF had no problems dealing with the T-62s whereas the Egyptians had little real success against the Israelis. Part of the problem – other than training – was the unfortunate problem that the T-62 had with its weapons system. Upon firing, the gun would then turn and elevate so that the automated casing ejector could grab the casing, open a hatch in the rear of the turret, eject the casing, and wait for the loader to feed in the next round. When the breech block closed, the gun would then return to its last position. Fine, if you hit your target; but if you missed, the gun went right back to where it missed. The time required for this was 15 seconds, during which an M60A1 would get off two to three rounds. (There was a T-62 Model 1966 in USAREUR which showed two hits from Israeli 105mm APDS rounds, each about 10" apart and either one fatal; this was a victim of the Chinese Farm battle.)

However, the IDF did note that whereas 2/3rds of Centurions knocked out were returned to service only 20% of the M48 and M60 series tanks were as fortunate.

The last gasp to date between the T-62 and the M60 took place during Operation Desert Storm in 1991. Here USMC M60A1 RISE tanks with explosive reactive armor fitted to them clashed with tanks from the Iraqi 5th Mechanized Division and 3rd Armored Division during the ground war. The results were not close, but both sides basically admitted it was due to the poor training levels of the Iraqi crews more than a failing of their equipment to stand up. While Iraqi fairy tales abound (one of the best involves a company of T-62s from the 16th Infantry Division that lulled a company of M1A1 tanks into point blank range, destroyed five and damaged nine while escaping with no losses) the actual results were that their forces were ineffectual.

The book covers these two episodes in great detail and does note where claims are not substantiated. There are a number of good photos and color drawings to illustrate the authors’ text. Both Lon and David are excellent authors and historians, and the book is a good read on these Cold Warriors and their fates.

Thanks to David Isby for the review copy.